DISCUSSION

This survey was the first step towards exploring the spectrum of COVID19 related problems reported amongst healthcare workers in the UK and to help decide the key scientific questions to address and the areas to prioritise for future research. This data is exploratory in nature and although there are important trends emerging, this will need to be taken in the context of a self-administered, anonymised, online survey. What Do The Results Indicate?

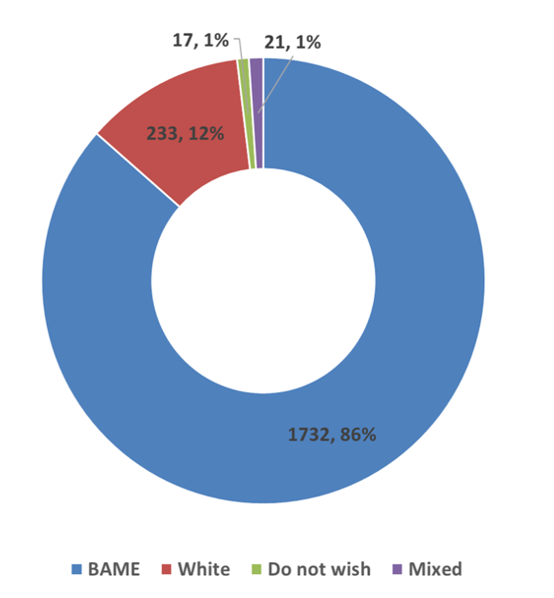

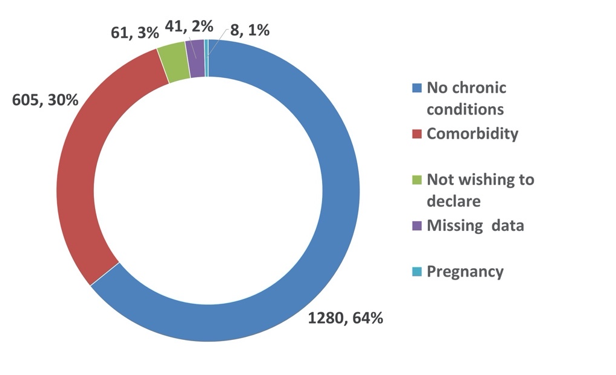

Firstly, it answers the fundamental question that being an HCW from a BAME community makes it 1.5 times more likely that one will acquire COVID-19. The confounding factors of age, regional spread of risk and facilities, co-existing co-morbidities, working in high risk settings are not shown to be significant in explaining this risk, at least in analysis of the results of this survey. Based on a range of rapid analysis of emerging data from the USA and UK, it is clear that there appears to be a differential spectrum of disease in BAME communities.

What is unclear at present are the reasons that may explain this observation. There is speculation about several clinical, social, economic, cultural and even religious factors that may contribute to a higher risk scenario. Unlike the population of Wuhan district in China, the population amongst the BAME communities in UK and USA remains hugely heterogenous. In the UK, HCWs come from several ethnic groups originating at different points in time from countries across the globe. Every social, cultural, clinical, educational and religious factors are bound to be widely variable. How would it be possible then to define and explore factors contributing to the observed high risk of COVID-19 in such a diverse group? Then hypothetically, it may also be possible that the rich commonality of experience as a BAME HCW in UK NHS, may have an over-riding contribution to the observed risk, far greater perhaps than the inherent factors based on origin. This in the context of this survey, is speculation and will need to be explored through well-designed and funded studies amongst HCWs.

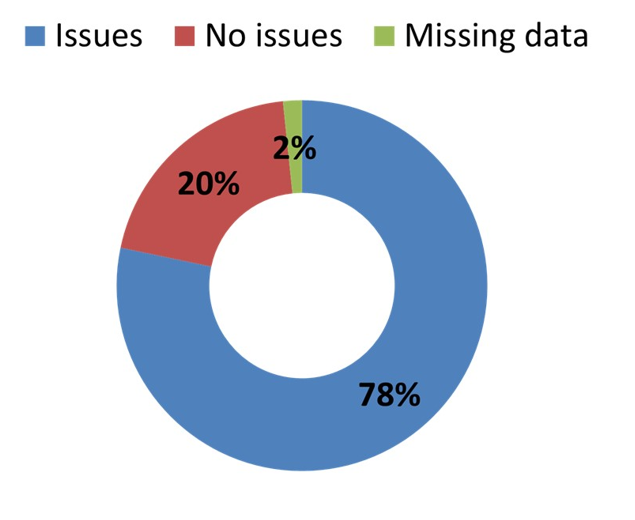

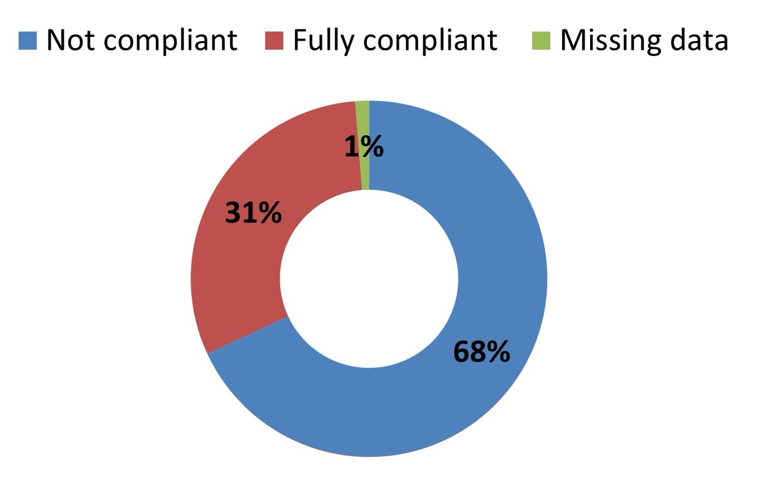

The second area of anxiety and concern is in relation to PPE. Our results indicate that a vast majority of respondents’ report having inappropriate PPE for clinical risk, of PPE being in short supply, being restricted in being able to use PPE or being reprimanded for using PPE. This is self-reported and may be subject to a different interpretation of the PHE, UK government and NHS guidance on the appropriateness of PPE for different clinical situations. Having said that, it is important to recognise the rising tide of professional opinion shared in professional groups, reinforced by surveys conducted by medical royal colleges and other professional associations which indicate that there is substance in this finding. Our data suggests an alarming majority of respondents report inadequate or inappropriate PPE. The report from a small proportion of respondents (n=64) of being reprimanded is a cause for further concern. Given the background of institutional racism, bullying, harassment, microaggressions and differential treatment of HCWs from certain minority and migrant groups, this finding is especially very worrying

14.

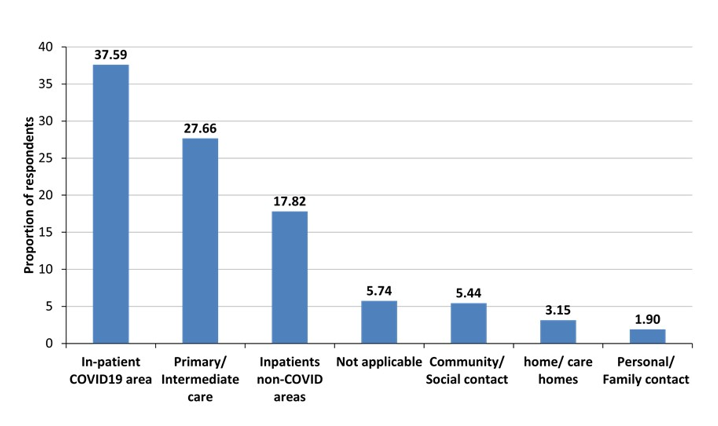

The third area of interest relates to the concept of social distancing guidance from the NHS and Public Health England for all. It is true that in most clinical areas, teams have to work in close quarters to provide care to patients. While, in an intensive care unit setting, this is provided by HCWs wearing PPE throughout the entire shift, this is not practical or possible in other less intense areas. There is thus a dichotomy in how individuals respond to the social distancing guidance. There is also a learned helplessness amongst staff on the inevitability of asymptomatic transmission between staff working in close quarters. In fact, the high prevalence of COVID-19 amongst staff seen in our survey and reported from Italy, Spain and France tells a similar story. It is unclear whether HCWs acquire infection while treating/ caring for patients or while working/ resting in close proximity to colleagues remains to be established. Our survey is not designed or powered to answer this question. However, our regression analysis indicates that for this population, it is unlikely that PPE or inability to comply with social distancing would have contributed to increased risk of COVID-19. Hence, more research is needed to decide what PPE is appropriate in each clinical risk scenarios.

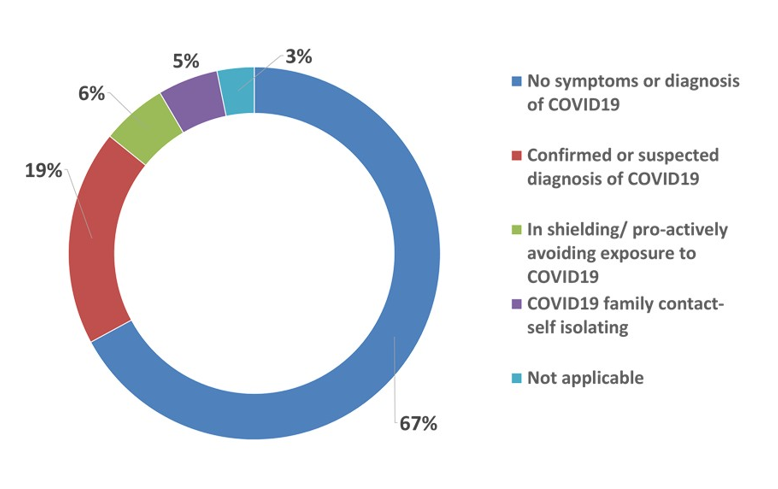

Finally, the question of self-isolation for HCWs with personal health risk, living with a vulnerable family member or having to forego self-isolation in the interest of one’s employment as well as for selfless service. Our results indicate that over 1/5 HCWs were unable to self-isolate despite the risk, hence exposing them to a higher risk of COVID19. Inability to self-isolate or choosing not to, appears to be a significant risk factor for COVID-19.

Accepting the weakness of a self-reported questionnaire, this is a worrying trend and perhaps requires further exploration with occupational health experts and human resources departments.

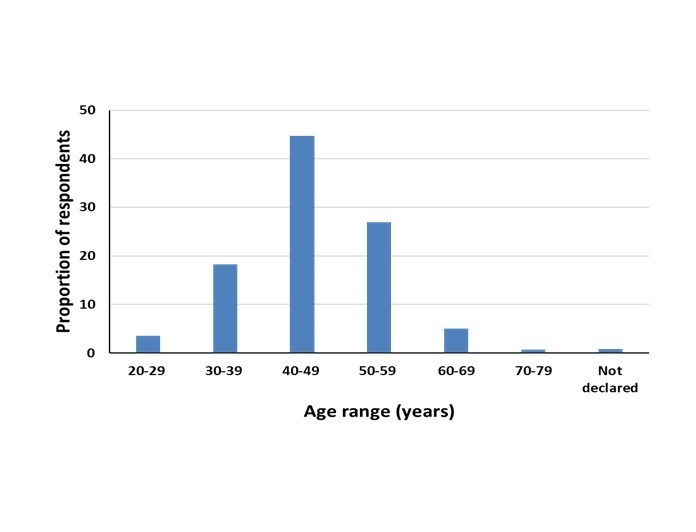

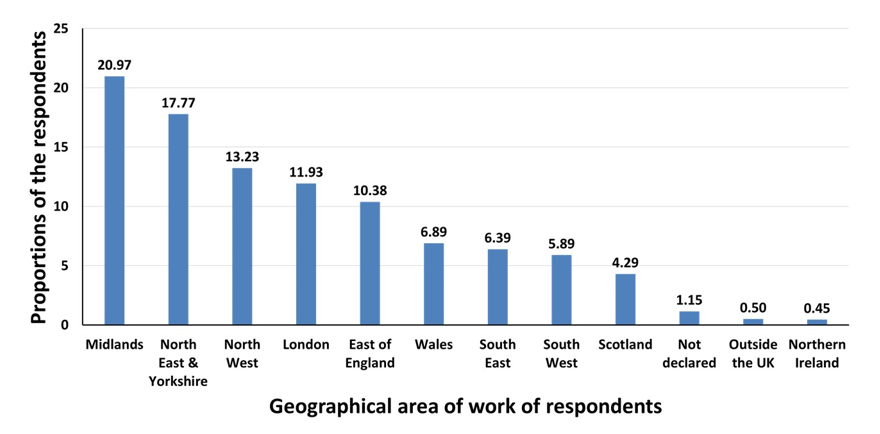

There are inevitably several limitations to the interpretation and conclusions one can draw from this data. Primarily, there is a possibility of a selection bias. By its nature of distribution i.e via BAPIO members and their associates connected through wide social networks, it is inevitable that the majority of respondents would be from a BAME or predominantly South Asian origin. The proportion of respondents reporting on their COVID-19 diagnosis or suspected diagnosis is also based on the recall bias of respondents. The survey did not use registration number or institutional email for verification in the interests of speed and breadth of data collection. This is in consonance with usual practice for online or telephone distant surveys of professionals where self-reporting of status is relied on. The researchers have no reason to believe that a respondent would have any reason to falsify their representations. The second safeguard was that the survey was sent via BAPIO membership database and encrypted social networks to verified recipients. The data distribution amongst professional groups, regional spread, age group and clinical sectors broadly represents the BAPIO membership and associates. Hence, although not a representation of the whole healthcare workforce in the UK, it does represent the BAPIO membership footprint.