Abstract

The British Association of Physicians of Indian Origin

(BAPIO) undertook a humanitarian project to come to the aid of a number of migrant

doctors who were in the UK to take the Professional & Linguistic Assessment Board’s

(PLAB) part 2 clinical examination, and had become stranded due to the lockdown during

the first surge of the COVID-19 pandemic. The BAPIO PLAB stranded doctors’ project

started as a serendipitous exercise in the third week of March 2020 with first a handful

of migrant doctors, until it reached a peak of 267 doctors from 19 countries, and

involved collaboration with multiple voluntary organisations, stakeholders, regulatory

agencies and governments.

There was no denying the complexity and intricacy of the

demands on the stranded doctors, but it was even more pleasing to witness how the

project team were more than ready to meet the challenges. Under the umbrella of BAPIO,

the project team doctors, who previously had barely known each other, took on all the

challenges - teaching, pastoral support, career advice, writing curriculum vitae,

finding food, accommodation and funds for those in need; organising professional

support, links with the General Medical Council, the High Commission of India and the

U.K. Home Office. The project was concluded on 19 September, with all the doctors either

returning home or making a decision to work in the NHS when conditions allowed them to.

It is not possible to know how many passed their PLAB

part 2 exams, but we estimated that over 50% did. The weekly virtual meetings, the

camaraderie, the scale of the project, and most importantly bringing it to a closure

without any major crisis, was only possible through sheer determination, understanding

the needs, professionalism, leadership and excellent communication. The lessons from

this project are important to illustrate the role of voluntary organisations (such as

BAPIO) and the effectiveness of having established collaborative networks with official

bodies and government agencies, for the future benefit migrant professionals.

Introduction

The British Association of Physicians of Indian Origin

(BAPIO) is a non-political, national, voluntary medical organisation that supports

members and other healthcare professionals through education, training, policy making,

and advocacy. Since its inception in 1996, BAPIO has actively promoted the principles of

diversity, equality and supported migrant doctors in their acclimatisation to the

healthcare sector in the UK. This support also extends to those who may have run into

professional or personal challenges. BAPIO in its philanthropic role contributes to

promoting access to better healthcare globally and responds to aid victims of natural

disasters across the globe. BAPIO has a history of campaigning and collaborating with

other organisations in the course of improving the UK National Health Service (NHS)

systems as well as directly and indirectly, promoting quality of care and safety for

patients. In this context, BAPIO is recognised by organisations and NHS doctors as a

body that can provide valuable assistance to doctors in difficulty, particularly those

who may have qualified abroad, or belong to under-represented minorities.

Stranded migrant doctors

BAPIO received notification on 19 March 2020 from an

Indian junior doctor that she was stranded and helpless after the General Medical

Council (GMC) announced on 17 March 2020 that it was cancelling the Professional and

Linguistic Assessments Board

1 (PLAB) part 2

examinations, with immediate effect due to an imminent lockdown imposed by the UK

government, amid concerns of safety for the candidates, examiners and staff. The

examination is a pre-requisite to foreign doctors gaining entry to the U.K. medical

register, so that they can practice or train here. Simultaneously, this stranded doctor,

who had been active on social media, had made contact with Dean of Royal College of

Psychiatrists via a tweet which was also picked up by two psychiatry trainees. The group

widened to include two other trainees in psychiatry and one Staff Grade doctor, and in

time following contact with BAPIO, two other doctors, a plastic surgeon in Manchester,

and a psychiatrist and Medical Director also in Manchester. The numbers of stranded

doctors contacting the ‘BAPIO PLAB family’, as they were later referred to, grew quite

quickly. Some urgency was placed on supporting these doctors by the Chair of the BAPIO

Institute for Health Research, , who wrote to the President and Chairman of BAPIO

informing us that there were 23 Indian doctors stranded in Manchester and urgent help

was required.

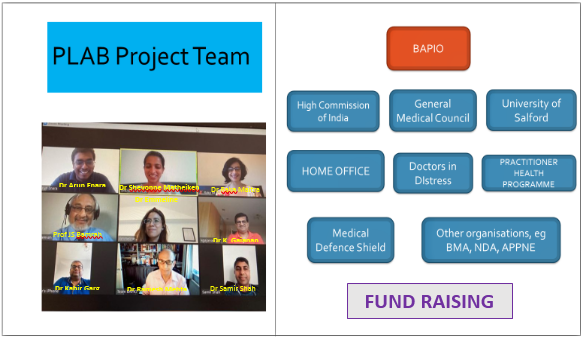

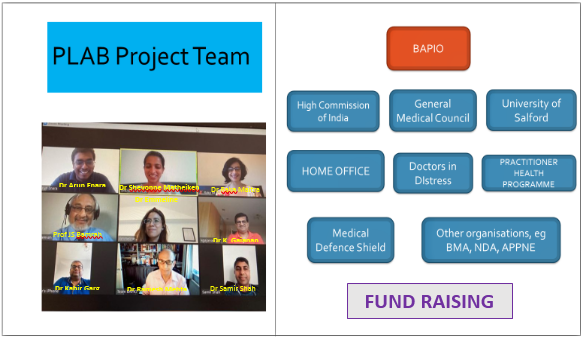

PLAB Project Team

In the overall scheme of the project there were

multiple needs for this group of doctors, and so internally it was necessary to

determine roles and responsibilities. The BAPIO PLAB project team comprised seven key

members and led by the Chair for the BAPIO Central Executive Committee. The first

objective for the project team was to have an understanding of the task, and to ensure

that there were good channels of communication. This must be prefaced with the fact that

all of the doctors who had formed the team were busy front line workers, and so this was

very much over and above their clinical and personal responsibilities. None of them had

been formally trained or assessed for any particular skills they brought into the task,

the assumption being that as they had volunteered or asked to volunteer and they had the

passion and commitment to support the stranded doctors. Interestingly perhaps, the

binding thread was the fact that all of the PLAB Project team members were themselves

international medical graduates. It is very likely that their own initial experiences on

arrival to the U.K. consolidated their commitment to the cause. Roles were not actively

assigned to the team members, except in the case of the role of ‘Salford project lead’

and Treasurer, so that there was financial governance in how funds were raised as well

as utilised.

Characteristics of the stranded doctors

The project team rapidly organised a rescue package as

it was obvious that the 23 doctors initial doctors who had been in touch were without

finances, estranged from family and friends, some were emotionally distressed and many

were without accommodation and insufficient means for obtaining food. It was also

evident that they were not the only ones in this predicament.

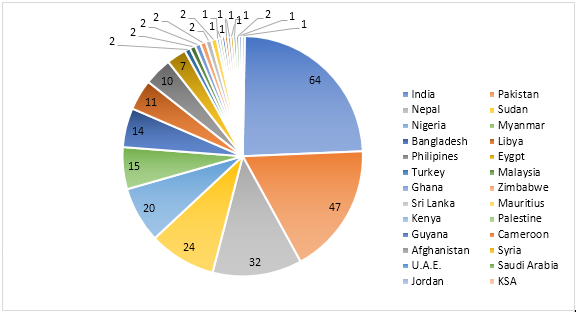

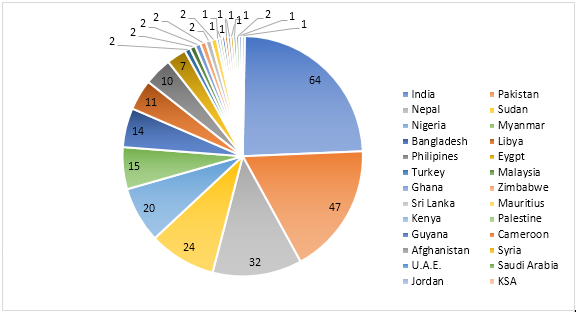

Fig 1. PLAB stranded doctors’ country of

origin.

Indeed, the numbers grew quite rapidly, so that within a

matter of weeks the total numbers of doctors supported was 267 who originated from 26

different countries (

Figure 1). As the pie chart demonstrates,

the majority of doctors came from the Indian subcontinent, with Indians constituting the

largest percentage of these doctors (24%), followed by Pakistanis (18%), Nepalese (12%

), Burmese (6%) and Bangladeshis (5%). From the African subcontinent, the Sudanese (9%)

and Nigerians (8%) were by far the largest group. The gender distribution was almost

evenly split with a slight preponderance of males.

There is no denying the complexity of this project.

Homeless, away from their countries and families, restrictions from Covid-19, short of

finances or access to funds, stuck in a foreign country there were many issues that

immediate and at crisis point for these stranded doctors. As well as all of that there

were a group of highly skilled doctors without jobs, and with additional frustration of

not being in their home countries to support colleagues at a time of this global

pandemic.

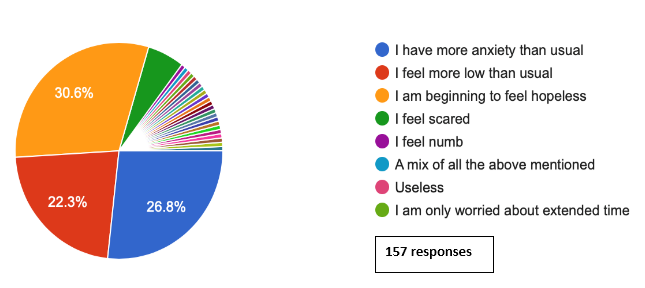

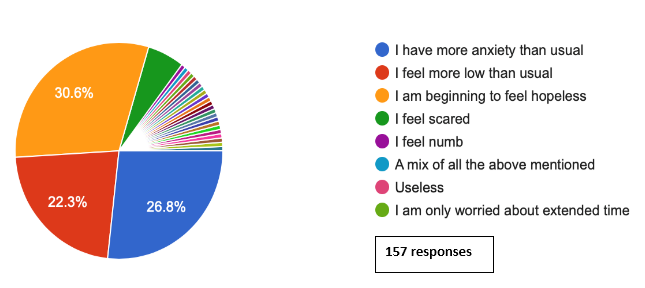

The impact on the mental health of these doctors was of

concern to the project team from the moment of contact, and as

Figure

2 demonstrates they were open in their admission to their experiences and

symptoms. The team were aware that these doctors would have more resilience than usual

and many were likely to be high achievers in their home countries, but nonetheless they

were away from their support networks, and the likelihood was that they would experience

significant issues of stress and anxiety

2. Fortunately,

all project team members were well equipped to support them or direct them to

appropriate channels, which in the end proved vital as none of them suffered a serious

mental health breakdown.

Fig 2. Emotional experiences of the stranded

doctors

Salford Project

BAPIO made arrangements with the University of Salford to

provide subsidised accommodation for those with the most urgent need. This was only

possible because of the established links with the Dean of the School of Health and

Society and since the University had to shut down and disperse its students following

the lockdown. The Salford lead took on the responsibility for allocating rooms,

arranging transport as well as giving them pastoral support. Food costs were met with by

BAPIO, and additionally free meals were delivered by the Shrimad Rajchandra Covid-19

S.A.F.E. initiative organised by Sonal Mehta and the local Sikh temple, whenever

possible.

In what was undoubtedly the most complex part of this

operation, it fell on the Salford Lead to provide personal care and support to all the

doctors that were in the Halls of Residence, and that sometimes included meeting their

religious needs, celebrating birthdays, organising medical care, keeping them

Covid-safe, holding their hands when they were distressed, and on many occasions,

sitting up with them late to prepare them for interviews

Figures

3 and 4. The Salford group were also an integral part of the

overall PLAB family, and therefore they benefited from the additional educational

training sessions as well as the liaison and collaboration that were undertaken with

external agencies.

Fig 3 and 4. Activities at Salford

accommodation

Collaboration is key to success (

Figure 5)

It was very clear from the outset that the project was

only viable if BAPIO could link up with several other agencies. The largest group of

junior doctors were from India (almost a quarter), so the strong links we had with the

High Commission of India (HCI) in London and Birmingham became a very useful axis for

providing them with rapid information about flights as well as Covid restrictions during

the flight as well as on arrival at the ports in India. So in this regard the virtual

sessions conducted with the Deputy High Commissioner and Consulate General in Birmingham

proved very useful as well as direct links with Mr Rohit Vadhwana, First Secretary

(Economics) of the Indian High Commission (London).

Fig 5. Essential areas of collaboration

A further crucial link was forged with the GMC, which

recognising the plight of the doctors, got involved from the most senior person in the

organisation, Charlie Massey, Chief Executive Officer, to those within the examinations

department, in particular Richard Hankins, Head of Examinations and Abi Boyson,

Assessment Change, QA and Customer Experience manager. There were a number of successes

in this collaboration, such as, obtaining refunds for the examinations that were

cancelled, free entry to the exams that were scheduled, bringing forward the date of the

first examinations to August rather than October, prioritising the exams for those

stranded in the U.K., and allowing the doctors to work as ‘Medical Support Workers’

which did not require medical registration but would have given them experience of

working in hospitals as well as being remunerated. However, there was little taking up

of this role due to hospitals being acute with Covid and because the doctors were

focused on exam preparations.

As illustrated above (

Figure 2)

this was in fact a stressful time for the doctors. Despite the 24/7 support available to

them there were signs that some needed counselling, and in the case of one individual,

psychiatric treatment. This was provided by NHS Practitioner Health

3 (PH), an organisation set up by Professor Dame Clare Gerada and one

with extensive experience in treating doctors with mental illness. This proved to be an

invaluable, confidential service that the doctors who accessed it appreciated very much

the personable treatment they received from the counsellors and doctors who were

treating them.

There was a pressing need to highlight the importance of

visas for these doctors. BAPIO undertook the responsibility of writing to the Home

Secretary with details of each of the doctors, after obtaining their consent, to ensure

that if require their visas would be extended beyond their expiry. This was done in

conjunction with other organisations such as the British Medical Association (BMA), the

Nepalese Doctors Association (NPA), the Association of Pakistani Physicians in Northern

Europe (APPNE) and the British International Doctors Association (BIDA).

Central to this operation was the need to raise funds.

Much of the funds were raised through two BAPIO campaigns. However, it became clear as

the global lockdown became extended to beyond the first three months that was

anticipated, that the funds would run dry. This information had spread to Nicky

Jayesinghe, Director of Foundation for Medical Research and Director of Corporate

Development, BMA. On her encouragement, BAPIO teamed up with a charity Doctors in

Distress

4 (DiD) with whose support were able to

successfully bid for significant funds from the BMA’s charitable arm. All the funds

raised went to accommodation and food, though there was also an emergency relief fund

for those doctors who were in financial difficulty.

Our internal collaborations within BAPIO were continuous,

and paid huge dividends. There was encouragement from officers and members of BAPIO. A

key role was played by the Medical Director of Medical Defence Shield (MDS) as each

stranded doctor was provided free indemnity from the MDS for up to a year.

Conclusion

There was consensus that the project would conclude on

19 September 2020, as per the expectation being that all the stranded doctors would have

either taken their PLAB 2 exams or had a later date to do this and hence would have

returned to their home countries.

There were no predetermined parameters for what success

would look like as that did not seem important in an emergent and evolving scenario.

From our point of view everyone was safe, they all felt financially and emotionally

supported, everyone had a roof over their heads, and no one was left hungry. From the

stranded doctors’ point of view, a major part of success would be passing their exams.

The GMC confirmed that of those who sat the exam, 79% had passed (the average pass rate

was 70.4% in the previous five years), though unsurprisingly the Salford group had a

slightly higher pass rate of around 81%. Some of the doctors had found training jobs in

the NHS, but the majority have now returned home with the intention of applying for jobs

at a later time.

BAPIO Covid-19 Award

Recognising the significant effort and contribution

the seven PLAB Project team members had made, often at the expense of their own personal

time, the BAPIO Awards Committee were unanimous in their decision that they were all

worthy of the Covid-19 award. This was symbolically collected on their behalf by the

Project Leader Raka Maitra, at a virtual awards ceremony during the BAPIO Annual

Conference on 21 November 2020, and individual awards were dispatched to each recipient.

Compliments and comments

This group of PLAB doctors were generous in their

praise for individual project team members as well as BAPIO as a whole. Multiple

messages on social media, via Twitter, WhatsApp, Facebook, were received as well as

emails, text messages and phone calls,. Some of these are replicated in the

table 1 below, and as well as these, there were videos of songs,

poetry, and all manner by which they showed the gratefulness of support they are

received at a time of distress and vulnerability.

Table 1: Comments and Compliments from the

Stranded doctors

Hi Dr Shevonne,

I got my results today and I

passed the exam. I do not know where to begin, except say that all this is

because of you. I’m here because of your hardwork and support. Me and the rest,

we couldn’t have been here if it weren’t for the core team’s, you all took us as

one of your own and helped us achieve this.❤

Words fail me Dr Shevonne, I do not

know what to say. Surely just saying thank you wouldn’t suffice .. |

| Friedrich Nietzsche one of my favourite

philosophers once said "he who has a WHY can bear any HOW”. Everyone here has a

why and the most noble "WHY" ever I think in history of mankind and it's the

betterment of your fellow man's life so I say this to all my BAPIO brethren

passed or not, you can bear any “HOW”, anything life throws at you, you will be

able to beat .... I wish you all, all the best in the world and congratulations

to everyone who passed and hang in there to everyone who hasn't ..Salam |

1st September 2020 and by grace of almighty I

passed my exam and am now in the process of getting my

registration.

I would like to specially thanks Dr Bhavana Chawda,

consultant psychiatrist and a member of BAPIO who gave me my first NHS

experience in the form a clinical attachment in psychiatry at Dorothy Pattison

Hospital. |

| Done with my exam and I am absolutely not sure

about the results. But, I am extremely glad that I have met such extremely cool,

caring and super inspiring people of this BAPIO team❤️. |

| Our last goodbye. We will miss you Dr Gaj. You have

been there through thick and thin for us. You truly are a Godfather for all of

us. We were blessed to have a guardian angel like you. We always longed for the

day you'd come and visit and eagerly text each other asking about your

whereabouts! Cant thank you enough for all that you’ve done. I believe we

started out as strangers and ended up being a family. Will definitely miss

Salford, especially Dr. Gaj. ❤️❤️❤️ |

| I am glad to inform you that I passed my

PLAB2 at my 4th attempt. Those who failed don’t be disheartened. If I can,

anybody can. Whenever JS said he took four attempts to pass PLAB, I had a rush

of adrenaline. I am really grateful to all the people around. |