INTRODUCTION

Every training and practising doctor

should become familiar with research processes and conduct, and where

possible have the opportunity to engage with research or pursue an

academic career as part of their professional choices.

1 However, in the UK, less than 10% of

doctors have a career in academia, at a time when the entire world has

woken up to the value of high quality research and researchers during

the current pandemic. Clinical academics play a vital role in advancing

our understanding and ability to treat existing and future

disease.

2 A diverse academic

workforce has been associated with greater scientific impact and

growth.

3 However, not all

individuals will progress in research and academia, with data showing

that in fact, diversity across clinical academics reduces as one

progresses through career milestones. Further analysis into diversity

demonstrates that a range of factors, (e.g. gender, race, disability)4

appear to contribute to limited progress in research and academia. In

recognition of these barriers to progression, the Research Excellence

Framework (REF) – (a system for assessing the quality of research in the

UK), places greater emphasis on organisations to demonstrate their

commitment to reducing inequality and increasing inclusivity. The Athena

Swan Charter was specifically developed to minimise the impact of gender

on career progression, with little doubt the programme did much to

highlight the problem of gender inequality in particular. All

stakeholders of research and academia have a statutory duty towards

reducing inequality and increasing inclusivity, including funding

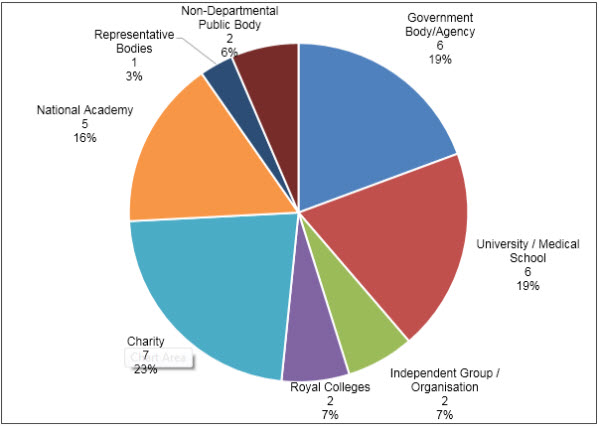

bodies. In this paper, we explore the extent to which, publicly

available information shared by key grant awarding bodies, report on

outcomes relevant for career progression (or along research journey) in

academia, and across individuals with a range of protected

characteristics, with a focus on ethnicity among healthcare

professionals.

EQUALITY, DIVERSITY AND INCLUSION

(EDI)

Equality is defined as treating

people fairly, impartially and without bias and creating conditions

in the workplace and society that value diversity, promote dignity

and encourage inclusion.

5 Diversity is an inclusive concept,

concerned with creating an environment supported by practices, which

benefit the organisation and all those who work in or with

it.

5 Diversity takes account

of the fact that people, whilst similar in many ways, differ

including (but not exclusively) on the basis of gender, age, race,

sexual orientation, physical ability, mental capacity, religious

belief, education, economic status, personality, communication style

and approach to work.

5 Inclusivity

means that everyone feels able to be themselves, valued and safe to

express different ideas, comfortable in raising issues and

suggestions to others, knowing that this is encouraged, and being

creative to try different ways of doing things. There is more

awareness about equality, diversity and inclusivity following the

2010 Equality Act, which legally protects people from discrimination

in the workplace, and in society.

6

DIFFERENTIAL CAREER TRAJECTORIES

In the UK, a clinical academic career

involves a complicated training programme, with competitive multiple

entry points across Foundation, Core and Specialist training, some of

which, but not all, may be integrated within clinical training

programmes.

13 However, across

all these entry points, there are marked differences in success, for

individuals who identify with a protected characteristic - starting with

selection into programmes and success in obtaining funding awards. These

differences continue beyond training, and extend to career progression

as well as development opportunities, or achievement of senior academic

posts. The factors that contribute to disadvantage are wide ranging and

are commonly considered to interact with each other.

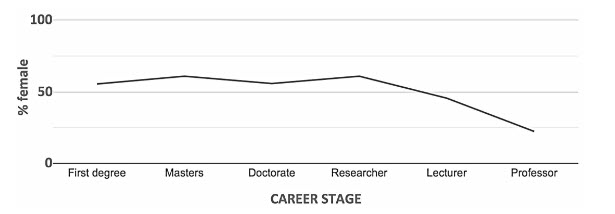

Gender

IThe Athena Swan Charter

14 was a system-wide programme to

address the structural inequalities facing women progressing with their

careers in science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM). As a

sector, higher education is relatively diverse, with almost equal

representation from men and women. However, the trend is different when

looking at contract type (fixed term vs. permanent) and appointment into

senior positions such as Readership and Professorships. These senior

positions in STEM were, and still appear to be male dominated (78.7%

male Professors)

15 Although >50% of early career researchers are women

in clinical medicine and biosciences, the proportion drops dramatically

at more senior levels.

16

Figure 1. The Athena Swan Charter attempted to

reduce some of this gender disparity in a number of ways.17 The 2011

announcement by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) to

only shortlist clinical academic departments with a ‘silver’ Athena Swan

award for (certain) research grants, resulted in an increase in the

number of female clinical academics in senior positions.

14 An

independent review of impact suggested the Charter was successful in

bringing about cultural and behavioural change for the benefit of women

in research and academia, but questioned whether the pace at the ‘most

senior levels’ was fast enough.

14

Addressing inequalities, especially where factors operate at multiple

levels, is difficult and the success of the Charter to address these

challenges appears to have been limited. There is evidence that gender

inequality may have improved for White women academics but not

necessarily for Black, and minority ethnic women, and in some instances,

White women may now have an advantage over Black and minority ethnic

men.

15,18 Often, more than one protected characteristics could play a

role in attainment; for example there are less than 20 Black Professors

in the UK 19 thus the combination of multiple protected characteristics

causing greater barriers - also known as intersectionality - is

important.

20

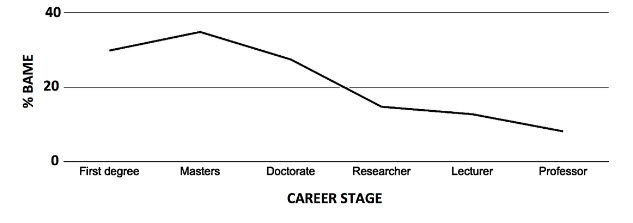

Ethnicity

Although individuals from Black and

minority ethnic backgrounds make up 34% of the total population of

doctors, they account for less than 17% doctors in academia.

22,23 In terms of senior leadership positions held by

individuals from Black and minority ethnic backgrounds in the NHS and

academia, the evidence demonstrates a lack of representation in both

contexts.22 Likewise, individuals from Black and minority ethnic

backgrounds are also under-represented across most levels in academia,

suggesting significant barriers still exist around progression along

career pathways

Figure 2.

The lack of representation appears to

extend across different institutions and organisation within research

and academia. Diversity data from the Research Council 2018 shows that

84% of the academic population in the Medical Research Council (MRC)

identify as White, with 4% and 1% belonging to Asian and Black

backgrounds, respectively. Further, 79% of the student population at MRC

was from a White ethnicity despite most medical schools having greater

proportion of their cohort, made up of individuals from Black and

minority ethnic backgrounds.

Success rates for principal

investigator funding across MRC grants and awards in 2016-17,

demonstrated a higher proportion of applicants identifying as White

(24.1%) compared to successful applicants from Black and minority ethnic

backgrounds (16.3%). Data describing successful new investigator

research grants from 2017-18 demonstrated higher success rates for

applicants identifying as White (24%) compared to applicants from Black

and minority ethnic backgrounds (7%).

24

Data from UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) in 2019 suggest the gap may

be widening with a higher success rate observed again among individuals

identifying as White (27%) compared to those identifying as Black and

minority ethnic (17%).

Data from the Wellcome Trust on grant

funding awards, identified the majority of successful applicants

identify as White (87%), and there was a consistent gap in success rates

over a three-year period between 2016-2019. Across this data, Black and

minority ethnic applicants were also under-represented among those who

were successful at obtaining more senior awards and fellowships.

25 Furthermore, the odds of non-White

applicants receiving funding were 0.68 times those of White

applicants.

25

The Higher Education Statistics Agency

(HESA) suggested that 91.2% Professors identified as White compared with

3.5% who identified as Asian and 0.6% who identified as Black.

15 Only 3.2 % of Heads of the

Institutions identified as Black and minority ethnic. Students from

Black and minority ethnic backgrounds were also less likely to progress

to scientific jobs after graduating than students identifying as

White.

16

Other protected characteristics

Reporting of outcomes from individuals

with protected characteristics can be limited due to need for protecting

anonymity when group sizes are small. Individuals with visible and

non-visible disabilities are under-represented in a range of work

settings, and the trend is no different in the scientific

workforce.

16 Only 2% of

UK-based applicants for Wellcome grants declared a disability at the

point of application (19% of working-age adults are disabled according

to the UK Government family resources survey 2016/17). There is some

data to suggest that people with a disability have less success at grant

award rate (13% versus 15%).

25 Although

not strictly a protected characteristic, deprivation is associated with

poorer outcomes especially among individuals with protected

characteristics. Individuals from a lower socio-economic backgrounds,

irrespective of ethnicity, are less likely to enter research and

academia, and are also less likely to progress in their careers as well

as take longer to get to professional level

16 Similarly, 2017 data from the Wellcome Trust,

suggested inequalities in entry to doctoral studies due to

socio-economic background, despite same attainment level in graduate

studies.

26

Protected characteristics and

intersectionality

Table 2: Funders represented

within the reports (see Appendix 2)

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

| Ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Gender |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Disability |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Age |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Socioeconomic

Background |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 2: In the

table above, the Blue colour shading signifies presentation of data

about the specific protected characteristic in the published report. The

Orange colour shading signifies the absence of data about the specific

protected characteristic in the published report. Reports here are

listed as 1-19; see

Appendix 3 for a full

named list of reports included. Gender was the most common protected

characteristic for which outcome data was presented (79%), followed by

ethnicity (53%), disability (21%) and then both age and socioeconomic

background (11%). Other protected characteristics, such as sexual

orientation, disability and religion were not specifically evaluated

across any of the reports.

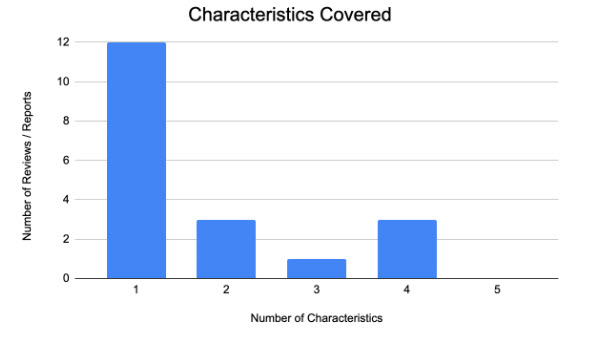

All 19 reports covered one or more of

four protected characteristics – gender, ethnicity, disability, age and

socioeconomic background

Table 2 . However, only

a few reports focused on more than one protected characteristic

Figure 5. Seven reports covered two or more

protected characteristics, whilst 4 reports covered three or more

characteristics, and only 3 reports covered four or more

characteristics. None of the reports covered more than five protected

characteristics.

Mapping of data from reports to factors

identified in the Bridging the Gap 2020 Thematic series.

27

Data identified from the 19 reports (see

Appendix 3) that mapped onto factors from

the Bridging the Gap 2020 Thematic series

27 associated with DA is presented below

Table 3.

Table 3:, The

colour Blue signifies presence of a factors from the Bridging the Gap

2020 Thematic Series.27 that were

presented in a published report. The colour Orange signifies absence of

any of those factors presented in a published report. Reports here are

listed as 1-19; see Appendix 3 for a full

named list of reports included.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

Total yes |

| Educational |

|

|

| Learning styles (problem

based/ taught/ self-directed) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

| Access to resources,

guidance or tutoring |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

| Schooling (independent

or state) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

| Impact of economic

status on educational opportunity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

| Parental/ family

(influence of parental education, support, expectation

or motivation) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

| Assessment (multiple

choice, viva, observed clinical assessments) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

| Impact of unrecognised

dyslexia or dyspraxia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

| Cultural |

|

| Linguistics (IELTS) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

| Previous life

experiences |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

| Conflict/ refugees |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

| Societal norms/

expectations (introvert vs extrovert) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

| Influence of reverence

of those more senior/in authority |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

| Segregation (wilful or

forced) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

| Bias |

|

| Segregation (wilful or

forced) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

19 |

| Impact of illness or

health impairment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

| Support |

|

| Family, friends |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

| Formal supervision |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

| Mentorship |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

| Networking |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

| Economic |

|

| Deprivation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

| Access to bursaries |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

| Cost of examinations/

preparation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

| Family responsibilities |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

| Others |

|

| Health (physical/

mental) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

| Immigration related

stresses |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

| Wellbeing, Stress and

Burnout |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

| Caring responsibilities |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

All reports documented the impact on

outcomes from factors such as age, disability, race and socioeconomic

status on the immediate outcomes in research and academia such as

failure to obtain a successful award or progress in a career. However,

no reports explored the subsequent short- or long-term impact of these

factors on the personal well-being, or physical and psychological health

outcomes of individuals, as a potential risk factor for further or

future disadvantage. Among the educational factors associated with

differential career outcomes,

27 access

to resources, guidance or tutoring were reported in 6 reports (32%).

Learning styles, schooling type, impact of economic status on

educational opportunity and impact of potential unrecognised

dyslexia/dyspraxia were only mentioned in one (5%) report.

Among the cultural factors associated

with differential outcomes,

27 no

reports investigated the role of linguistics, conflict/refugee status or

segregation as a cause for DA in a research or academic context. Four

reports noted the influence of accessing support from a senior (21%) and

2 reported noted societal norms/expectations (11%). No reports

investigated the impact of limited networking opportunities in a

research and academic context. Four reports (21%) investigated the

availability of formal supervision and 6 (31.6%) mention accessibility

to mentorship as contributing factors.

Among the economic factors associated

with differential careers,

27 the impact

of deprivation, access to bursaries, cost of examinations/preparation

and a family responsibility was investigated in part. Access to

bursaries was reported in 3 reports (16%), with family financial

responsibility reported in 2 reports (11%). Deprivation and cost of

exam/exam preparation were also reported on one occasion.

Within the factors classed as “other”

were immigration related stresses, wellbeing/stress/burnout and caring

responsibilities.

27 Immigration

related stress was not reported on as a potential driver of differential

carers. Health and wellbeing/stress/burnout was only reported on in 2

reports (11%). That said, caring responsibilities was reported in 7

reports (37%).

DISCUSSION

This rapid scoping review was

undertaken to evaluate the extent to which funding bodies reported

equality, diversity and inclusivity outcomes, with a specific focus on

evidence of DA among individuals with protected characteristics and the

impact of intersectionality among individuals from Black and minority

ethnic backgrounds. The findings demonstrated DA across funding body

outcomes is also prevalent, and the impact of multiple protected

characteristics (e.g. gender and ethnicity) appear to particularly

amplify the achievement gap between Black and minority ethnic and white

individuals in research and academia. Furthermore, the mapping data

presented in the published reports with factors associated with DA

identified in the Bridging the Gap 2020 Thematic Series document

27

demonstrate an ‘awareness gap’ between funding bodies and individuals

from Black and minority ethnic backgrounds about barriers to success as

well

Table 3. The findings from the review

highlight a number of issues that need further exploration and

discussion with all stakeholders of research and academia in the

UK.

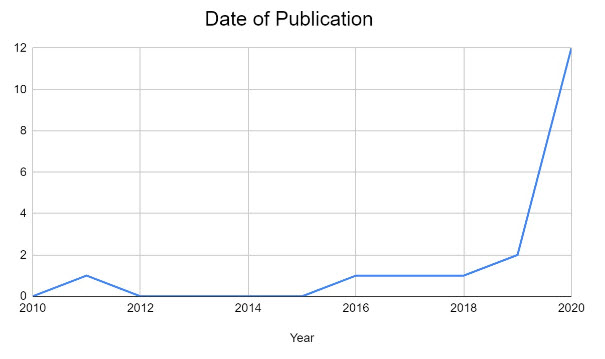

Broadening the EDI lens to consider the full range of career limiting

factors

Firstly, there is a need to reflect

over the starting point for this scoping review and the lens through

which it was undertaken – equality, diversity and inclusivity (EDI).

Although the review demonstrated greater awareness of EDI over the last

decade, many of the reports have only been conducted in the last year or

so, and thus few reports have been able to be repeated, to evaluate

change in outcomes. Likewise, across many reports, gender outcomes have

been the focus of improvement, but in some respects, gender appears to

have been conflated with EDI in the broadest sense, more so than

ethnicity or disability. This foregrounding of gender over and above

other protected characteristics is multifactorial and likely includes

interventions by funders such as NIHR after 2011, stipulating specific

conditions related to gender targets before awarding funding to

organisations.

14 This is perhaps unsurprising given the

focus on gender through statutory gender pay gap reporting since 2017,

and the Athena Swan Charter. This target-driven approach has led to

positive change with respect to actions to progress gender equality,

though outcomes are still far from equal, especially at senior levels.

Conversely the danger of focusing on one particular characteristic over

another is the risk of fuelling a sense that one group's injustice is

more or greater. For this reason, there is a real need for funders and

stakeholders to consider all programmes of work on EDI within their

organisations, and to evaluate the extent to which they acknowledge

individuals across the range of protected characteristics.

Another reason for the focus on gender

rather than other protected characteristics such as ethnicity, may

involve a degree of blindspot bias.

50 Given the lack of general

awareness and/or data collection about EDI within research and academia,

conceptualisations of inequality among funding bodies appear to focus on

gender rather than being fully inclusive of individuals belonging to

groups with all protected characteristics. Further, this general bias as

a whole appears to have led to a general lack of recognition about

broader EDI issues, especially for people from Black and minority ethnic

backgrounds.

51,52 In fact, the notion of ‘White privilege’ was not

reported in any report further suggesting a lack of awareness, or

understanding about this concept despite the recognition of it in the

wider literature,

53 despite many higher education institutions

committing to Advance HE’s Race Equality Charter (REC).

54 The same is no

doubt true for other protected characteristics where there are workplace

initiatives to advance inclusivity such as Disability Confident and

Stonewall Diversity Champions. This is perhaps due to fatigue of one

program but also not having similar linked intervention by funders such

as NIHR for Athena Swan Charter.

14

The interaction of different protected characteristics should be

focal in advancing inclusive research and academic careers for

doctors

Secondly, and related to the concept of

protected characteristics, is the notion of intersectionality

20 Defined as 'the interconnected

nature of social categorizations such as race, class, and gender as they

apply to a given individual or group, regarded as creating overlapping

and interdependent systems of discrimination or disadvantage’,

intersectionality is a particular issue for individuals from Black and

minority ethnic backgrounds but also is important for individuals from

White backgrounds. Although well described in wider literature to date,

the issue of intersectionality was conspicuous by its absence among

research and academics in this review. The problem appears to strike a

chord among Black and minority ethnic doctors when describing their

experiences of overcoming barriers in research and academia. For

example, whilst addressing gender inequality, will no doubt help Black

and minority ethnic women progress in research or academia, there is

little doubt that Black and minority ethnic women also face additional

barriers as a consequence of their ethnicity. Put another way, ethnicity

was one less barrier non- Black and minority ethnic women had to face,

or one more barrier Black and minority ethnic women had to face in order

to advance in research and academia. However, the general lack of

understanding or acknowledgement of the problem demonstrated across

reports suggests much progress needs to be made in this area.

Many of the reports focused on factors

such as gender, ethnicity, disability, age and socioeconomic background.

These factors were most likely chosen because they are easy to measure,

given many funders and stakeholders already have this type of data. The

usefulness of this data is limited for a number of reasons. Ethnicity is

often used as a catch all term for any individuals from Black and

minority ethnic backgrounds, and ignores the observation that there is

as much, if not more variation between different Black and minority

ethnic versus non-BAME backgrounds. Outcomes in higher education are not

to be the same for Black people or people who self-identify as

Bangladeshi or Pakistani, as compared to people who self-identify as

Indian, British Indian or Chinese, with the latter achieving better

outcomes on some measures than the reference non-BAME group.

55 The homogenisation of individuals

from Black and minority ethnic backgrounds into one ethnic category does

little to acknowledge the significant variation among people in this

group, as well as their specific perceived barriers in research and

academia. This form of categorisation can also lead to reductionist

interventions to mitigate the impact of unconscious bias are undermined

since the problem - ethnicity - has been oversimplified to the point

where it doesn’t really mean anything that matters. Whilst there is an

acknowledgement that the numbers may preclude meaningful analysis in

variation, and so some aggregate data is required, more transparent and

considered analysis is required. Hence, future analysis using

disaggregated ethnicity categories (for both Black and minority ethnic

and White) would highlight where the widest gaps are.

The need to acknowledge personal and socio-cultural factors may

influence the BAME attainment gap in ways non-BAME groups may not

fully understand so should take time to do so

Prior to this review, the Bridging the

Gap programme of work highlighted many possible factors which impact

differential outcomes in dual academic and research careers for

doctors.

27 These factors are

span multiple domains including education, culture, and social

circumstances, yet many of the reports reviewed in this paper did not

appear to acknowledge their existence or effect on progression for

doctors from Black and minority ethnic backgrounds. For example, none of

the reports acknowledged the significant positive influence of parents

and family on the motivation levels and resilience among doctors from

Black and minority ethnic backgrounds. Instead beyond the research and

academic context, there has been negative stereotyping that

characterises the families of Black and minority ethnic doctors as

coercive and demanding on individuals.

56 Despite there being a large body of literature

demonstrating the value of parental or family support to individuals for

achieving many academic and non- Black and minority ethnic doctors

appear not to be provided specific support with linguistics even when

there is evidence sophisticated communication support and coaching may

improve outcomes for Black and minority ethnic doctors at

assessment.

57 In contrast, when

individuals with specific learning require support due to various

information processing challenges they face, organisations are prepared

to fund it without too much delay. When Black and minority ethnic

doctors struggle with language, dialect and academic writing, the

perceived response is often for individuals to work harder or attend

extra training rather than a form of developing coaching or performance

enhancement intervention,

58 thus

focusing on the deficit model rather than looking at wider institutional

change. Even for some factors such as immigration and visa related

issues, particularly unique to non-UK Black and minority ethnic doctors,

there was no acknowledgement of this challenge as a factor affecting

research and academic outcomes, demonstrating the general lack of

awareness or blindspot among funders and stakeholders about these

problems.

Avoiding simplistic population or BAME-based interventions for

overcoming barriers related to attainment gap

The findings from the review demonstrate

the very real gap between the perceptions of individuals from Black and

minority ethnic backgrounds about the factors preventing them from

achieving their full potential, and the focus of stakeholders such as

funding bodies about drivers of progression in research and academia and

their role in addressing this. Interventions for addressing EDI issues

seem to focus on the ‘bias’ as the main cause of the doctors from Black

and minority ethnic backgrounds progressing in their careers. Although

de-biasing interventions are well-reported in the wider literature,

their effectiveness for improving individual outcomes for doctors from

Black and minority ethnic backgrounds remain unclear. Furthermore,

de-biasing interventions or unconscious bias training assume that ‘bias'

is something that can be trained out of those who demonstrate it. The

extent to which there is evidence that such strategies are able to

achieve this outcome in any meaningful or long-term way is also lacking.

Conversely, doctors from Black and minority ethnic backgrounds who

report being subject to forms of bias, are often referred to

communication, leadership or resilience training courses. The assumption

underpinning all of these interventions is that individuals can be

trained to become resilient to the problem however there is little

evidence in the wider literature for effectiveness of these approaches

either. These types of organisational interventions or responses infer a

deficit model within the individual rather than acknowledgement by

funders and stakeholders of a problem within the system being the cause

for poorer outcomes in research and academia among doctors from Black

and minority ethnic backgrounds.

Moving away from EDI ‘projects’ to sustained and embedded practice

Many of the reports included in this

review also appeared to detail single pieces of work or projects related

to EDI, rather than a long-term programme of work committed to achieving

change in research or academia for individuals with protected

characteristics. This scoping review evidenced elements of positive

practice from funders about their focus on EDI, mostly in relation to

gender, but the opportunity now exists for widening the breadth and

depth of those EDI programmes of work. Whilst there was a particular

absence of attention towards intersectional factors that could be career

limiting, the findings from this review may help develop specific,

measurable actions that can help to reduce DA in a meaningful way. The

success of narrowing gender disparity was likely driven by a statutory

focus on the gender pay gap reporting as well as the Athena Swan

Charter. There is now an opportunity to fully embrace and embed the REC

into policy making at all levels across research and academic

environments.

MOVING FORWARD

As a result of this review, a number of

areas have been identified for further discussion with funders and

stakeholders in small-group workshops to guide further research and

policy developments.

The collection, analysis and sharing of

data relating to progress in research and academia for people with

protected characteristics

Possible areas for exploration

include:

- Creating a uniform framework of what EDI data should be

collected by stakeholders and organisations including funding

bodies

- Longitudinal reporting of outcomes for all people, including

those with protected characteristics from selection into

academic training pathways through to grant/funding awards and

career progression

- Working together with HEIs and NHS Trusts to develop a

framework for monitoring their own data and ensure reducing the

attainment gap is a priority

- Meaningful reporting of data analysis incorporating effect of

intersectionality and multiple protected characteristics as

compared to single or few.

- Likelihood of COVID19

The development of EDI strategy that is

inclusive for all, and not just exclusive to the few

Possible areas for exploration

include:

- EDI strategy development that accurately reflect the challenges

faced by people across the range of protected characteristics

- EDI strategy that includes training of staff to raise awareness

about the barriers faced by people with protected

characteristics, e.g. BAME doctors as reported in the wider

literature

Representation from people with

protected characteristics across leadership and management structures

Possible areas for exploration

include:

- Efforts to increase representation from people with protected

characteristics feeding into committees and decision making

policy within your organisation

- EDI strategy that includes training of staff to raise awareness

about the barriers faced by people with protected

characteristics, e.g. BAME doctors as reported in the wider

literature

- Positive action to accelerate the pace at which representation

is improved at senior academic and research levels e.g. targeted

fellowships for mid-career etc.